In 2020 and now 2021, a large number of citizens found themselves homebound. While the stay-at-home orders were a novel experience for most people, the isolation of individuals with a contagious disease has a long history. While it is true that many suffered inconvenience and the disruption of normal routines, the modern home is so well equipped we weren't lacking for much in the way of necessities and comforts. Additionally, those quarantined at home were able to venture outside to replenish supplies or through delivery is needed. It has not always been so easy. The worst outbreak of bubonic plague in early modern England took place in London in 1665. Considering this experience can give us pause to give thanks that we live in the early twenty-first century.

In the first part, Victor Gamma looks at plagues in 17th century England and how people in London during the 1665 Great Plague endured quarantine.

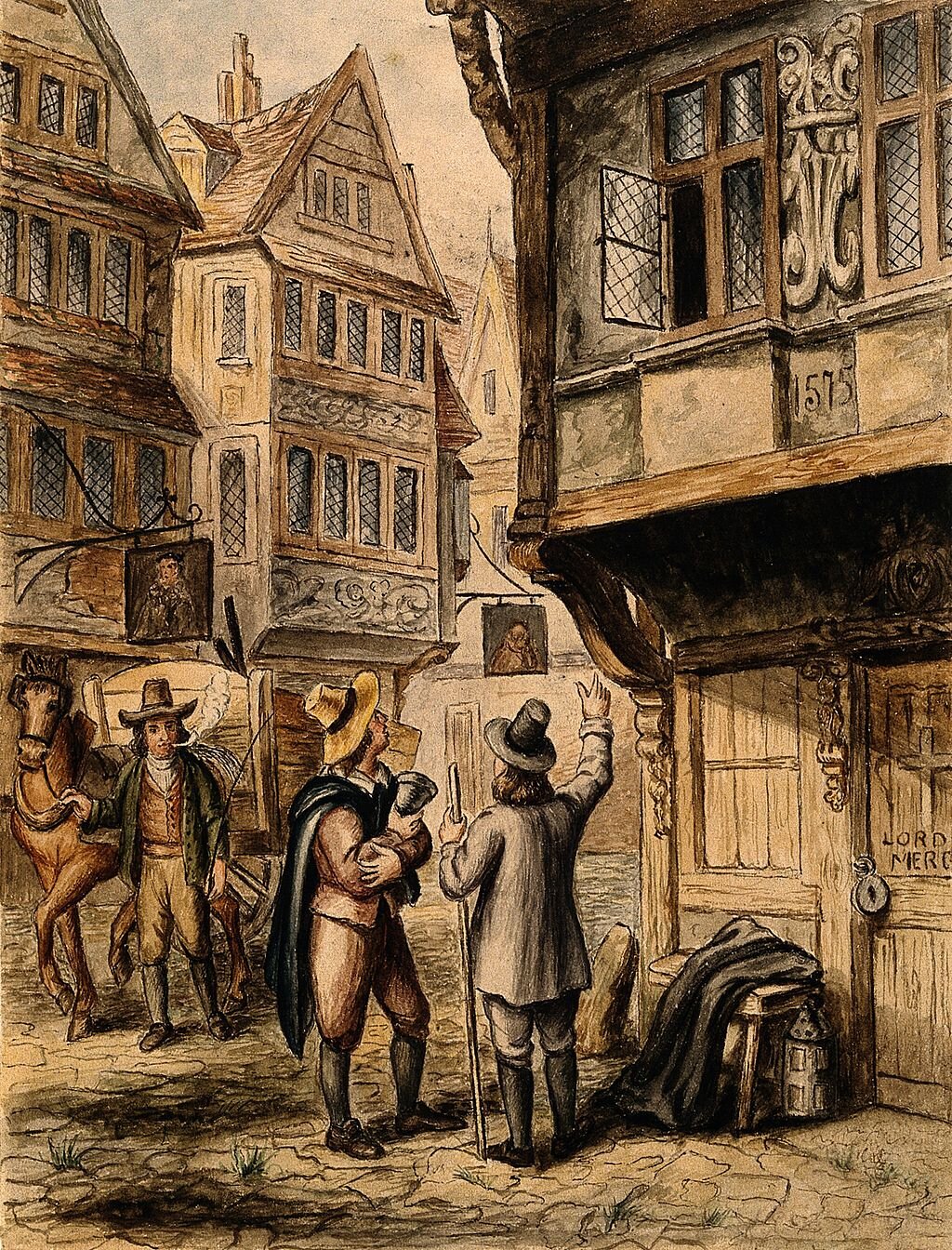

A cart for transporting the dead in London during the 1665 Great Plague. Source: Wellcome Trust, available here.

From 1574 English law stated that members of a house containing a plague victim were not allowed, "to come abroad into any street, markete, shoppe, or open place of resort." If any one from an infected house needed to come out for any reason they were required to carry a white rod, at least two feet in length for all to see. At each outbreak of plague the College of Physicians met to formulate a plan of action. This would include written and published advice on managing a pandemic. This had taken place in the 1580s, 1630 and 1636. In April of 1665, knowing an epidemic was likely, the College of Physicians recommended a two-fold approach to containing the spread of plague: isolation in pesthouses or quarantine of infected persons in their homes. A pest or plague house was a structure used to forcibly quarantine infected individuals. One obvious measure was the isolation of infected individuals or those suspected of carrying the dreaded disease. The weak infrastructure and resources of the time made household quarantine a necessity. Some parishes, in fact, had only recently begun a serious effort to construct an adequate number of pesthouses. To illustrate the sluggish nature of plague response: in St. Martin’s a well was dug for a pesthouse on July 24, 1836, 4 months after the plague made its appearance.

1665 plague

The plague of 1665 was to dwarf the earlier plagues. There was no way to know this, of course, but to meet the looming crisis the College began regular meetings in May 1665 at the request of the Privy Council. The Council specifically enjoined the Physicians to review the previous advisory statements and add anything they deemed would improve the effectiveness in stopping the spread of this new outbreak. Within two weeks, on May 25 they had a “little book” of 44 pages published entitled “Certaine necessary directions, as well for the cure of the plague, as for preventing the infection: with many easie medicines of small charge, very profitable to his Majesties subjects.” The Physicians saw no reason to change the practice of shutting up infected people in their houses. The 1636 advice had read:

If any person shall have visited any man, knowne to be Infected of the Plague, or entered willingly into any knowne infected house, being not allowed: the house wherein he inhabiteth, shall be shut up for certaine dayes by the Examiners direction

This direction was given in spite of the fact that in 1630 the Privy Council had recommended pesthouses as a “better and more effectual course” to reduce the plague. In the Great Plague, the order to shut up all infected houses was ordered officially on July 1, 1665. The only way a person in an infected house could move legally was to go to another property they themselves owned or to a pesthouse. Once an infected house was identified it was to be “shut up” for forty days. Records indicate that this policy was quite unpopular and that residents attempted to avoid this fate as often as possible.

The Privy Council handed its directives to the Lord Chief Justice, who in turn gave it to the magistrates. Attempts were made to keep the proceedings secret but word of mouth soon gave wings to the terrifying reality that another outbreak of the bubonic plague was at hand. Besides, a member of the Royal Society named John Graunt published a regular report of deaths in the city, called “Bills of Mortality.” For a subscription of four shillings a year anyone could read these and easily see that London was in the throes of a dreaded “visitation” - and this one promised to be worse than that which held the City in its grip just ten years earlier.

Identifying the Sick

Once someone in a household died, the government sent out “searchers” to ascertain the cause of death. This would come in the form of an old woman. It was her job to report her findings to the parish clerk and especially to alert authorities if plague was present so that the house might be shut up. Usually old women who had no other means of support filled this occupation. This offered some hope to the victim’s family of not being labeled as infected of plague because these old women were notoriously unscientific in their methods. First, they had no real training in medical diagnosis. Typical opinions rendered by the searchers on cause of death included vague terms such as "frighted", "rising of the lights", or "suddenly." Anyone at all elderly was most likely reported as dying of "age." To mitigate this problem, the government directed surgeons to assist the women with their work. The accuracy of reporting was undermined, though, by corruption. The women were quite susceptible to bribery. These women were invariably of the poorer classes and they were not likely to be fussy about the rules if their palms were warmed with silver. The reality was, they almost needed bribes to keep body and soul together. This hard fact outweighed the solemn oath they had taken to "faithfully, honestly, unfeignedly, and impartially" report the cause of death. If there was a danger of the searchers reporting an instance of plague, a few shillings or a bottle of gin would often suffice to persuade the woman to change her verdict. In spite of the reputation of the searchers, many families felt compelled to take any desperate measure which might avoid the living hell of home imprisonment. A family with a sick member would often attempt to disguise signs of plague as much as possible. For example, to mask the symptoms they might hold a piece of ice or a cloth soaked in cool water against the face of the deceased in hopes of hiding signs of inflammation.

Despite these efforts, thousands of houses were marked as infected or as “plague” houses. This would include everyone in the home, infected or not. The “clarke” or sexton of each parish was then directed to post a sign on the house which read “Lord Have Mercy Upon Us.” A large cross of one foot in length would be nailed or painted onto the front door. The twenty-day countdown to the end of the quarantine would commence either when all infected persons were cured or carried off dead. Families tried to reason with the magistrate that if, of the twenty people in the house, only one was sick - why should all be imprisoned within the walls? These pleas normally fell on deaf ears. If any member of that household appeared in public they would be liable to a jail term of forty days or a fine of £5 (some $1,100 in today's money). Many attempted to bribe the authorities or flee before the watchmen arrived.

Quarantine

Once marked, the inhabitants were now prisoners in their own home until the property was declared free from infection for at least twenty days. Unlike our own time, there would be no trips to the store to stock up on supplies and no ordering of delivery service. Far from it, for most people would avoid these houses at all costs. Word spread rapidly about which streets had “shut up” houses. Samuel Pepys noted in his diary that even when a distance from a shut up house he would sometimes be warned away: "...a gentleman walking by called to us to tell us that the house was shut up of the sickness. So we with great affright turned back, being holden to the gentlemen; and went away." Those people who were compelled to walk the street that contained plague houses would stay in the middle of the street to avoid infected persons and any odors emanating from the house, which were believed to carry plague. As a further incentive to keep people away, the law also stated that persons guilty of unauthorized entering of an infected house would have their own house shut up.

Aware of the large number of attempted escapes, government directives were very specific about enforcement. The unpublished minutes of the Privy Council contained an order that “whosoever shall do the contrary shall be shutt up in the same house as in an infected house for soe long a time as the … Justices of the Peace shall (think) meete.” Watchmen were sent to guard the structure for the length of the quarantine. An armed guard would be posted outside the house with orders to prevent anyone from leaving. In the evening a night watchman would come to his relief. They would most likely be armed with a sharpened halberd. The watchmen were not to be merely guarding the house; they were instructed to give aid as needed, even at their own expense. Additionally, parishes did have systems in place to minister to needs of shut up houses. In practice, of course, this generosity did not always occur and the family would sometimes have to decide whether to starve or sell their few possessions. They would begin gathering up anything of value; cooking utensils, candles, items of furniture, even floor mats. These items would be handed through the window to the watchman. Before departing to sell the items, the watchman would go all around the house nailing up all doors and windows. Could the watchman be trusted? The answer too often came when he returned but a pittance for the few pitiful goods offered, claiming he was only able to sell the candles. Some attempted to trick the guards into leaving his post on some pretense. If the watchman were simple enough to be fooled, the inhabitants could break off the lock while he was gone, gather whatever items could be carried on the door or through some other means, and escape. To avoid that possibility, the guards placed padlocks and bolts on doors and shutters.

Now you can read part 2 on Plague houses and whether home quarantine was worth it here.